In the previous chapter you learnt that the people in the prehistoric times used tools and weapons made of stone. Later man started using metals. Copper was the first metal to be used by man for making tools. Gradually several cultures developed in Indian subcontinent which were based on the use of stone and copper tools. They also used bronze, a mixture of copper and tin, for this purpose. This phase in history is known as the Chalcolithic chalco-Copper; lithic-Stone) period. The brightest chapter in the Chalcolithic period in India is the Harappan civilization which is also referred to as the Indus Valley civilization.

Harappan civilization was discovered in 1920–22 when two of its most important sites were excavated. These were Harappa on the banks of the river Ravi and Mohenjodaro on the banks of the Indus. The first was excavated by D. R. Sahani and the second by R.D. Bannerji. On the basis of the archaeological findings the Harappan civilization has been dated between 2600 B.C–1900 BC and is one of the oldest civilizations of the world. It is also sometimes referred to as the ‘Indus Valley civilization’ because in the beginning majority of its settlements discovered were in and around the plains of the river Indus and its tributaries. But today it is termed as the Harappan civilization because Harappa was the first site, which brought to light the presence of this civilization. Besides, recent archaeological findings indicate that this civilization was spread much beyond the Indus Valley. Therefore, it is better it is called as the Harappan civilization. It is the first urban culture of India and is contemporaneous with other ancient civilizations of the world such as those of Mesopotamia and Egypt. Our knowledge of the life and culture of the Harappan people is based only on the archaeological excavations as the script of that period has not been deciphered so far.

By around 2000 BC several regional cultures developed in different parts of the subcontinent which were also based on the use of stone and copper tools. These Chalcolithic cultures which lay outside the Harappan zone were not so rich and flourishing. These were basically rural in nature. The origin and development of these cultures is placed in the chronological span between circa 2000 BC–700 BC. These are found in Western and Central India and are described as non-Harappan Chalcolithic cultures

OBJECTIVES

After seen this video, you will be able to:

- explain the origin and extent of the Harappan civilization;

- describe the Harappan town-planning;

- understand the Harappan social and economic life;

- discuss the Harappan religious beliefs;

- explain how and why did the civilization decline;

- identify the Chalcolithic Communities outside Harappan zone;

- explain economic condition and settlement pattern of these Chalcolithic communities.

The harappan civilization Nios Class 12th history 3rd Chapter

ORIGIN AND EXTENT

The archaeological remains show that before the emergence of Harappan civilization the people lived in small villages. As the time passed, there was the emergence of small towns which ultimately led to full fledged towns during the Harappan period. The whole period of Harappan civilization is in fact divided into three phases: (i) Early Harappan phase (3500 BC–2600 BC) – it was marked by some town-planning in the form of mud structures, elementary trade, arts and crafts, etc., (ii) Mature Harappan phase (2600 BC–1900 BC) – it was the period in which we notice welldeveloped towns with burnt brick structures, inland and foreign trade, crafts of various types, etc., and (iii) Late Harappan phase (1900 BC–1400 BC) it was the phase of decline during which many cities were abandoned and the trade disappeared leading to the gradual decay of the significant urban traits.

The location of settlements suggests that the Harappa, Kalibangan (On R GhaggarHakra generally associated with the lost river Saraswati), Mohenjodaro axis was the heartland of this civilization and most of the settlements are located in this region. This area had certain uniform features in terms of the soil type, climate and subsistence pattern. The land was flat and depended on the monsoons and the Himalayan rivers for the supply of water. Due to its distinct geographical feature, agro-pastoral economy was the dominant feature in this region.

TOWN PLANNING

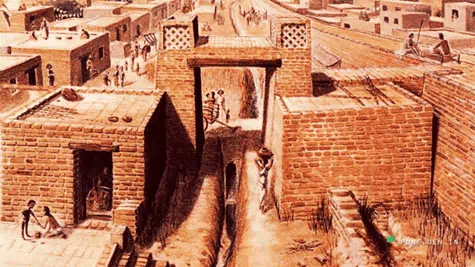

The most interesting urban feature of Harappan civilization is its town-planning. It is marked by considerable uniformity, though one can notice some regional variations as well. The uniformity is noticed in the lay-out of the towns, streets, structures, brick size, drains etc. Almost all the major sites (Harappa, Mohenjodaro, Kalibangan and others), are divided into two parts–a citadel on higher mound on the western side and a lower town on the eastern side of the settlement. The citadel contain large structures which might have functioned as administrative or ritual centres. The residential buildings are built in the lower town. The streets intersect each other at right angles in a criss-cross pattern. It divides the city in several residential blocks. The main street is connected by narrow lanes. The doors of the houses opened in these lanes and not the main streets.

The drainage system of the Harappans was elaborate and well laidout. Every house had drains, which opened into the street drains. These drains were covered with manholes bricks or stone slabs (which could be removed for cleaning) were constructed at regular intervals by the side of the streets for cleaning. This shows that the people were well acquainted with the science of sanitation.

SOME MAJOR STRUCTURAL REMAINS OF THE HARAPPAN TOWNS

At Mohenjodaro the ‘Great Bath’ is the most important structure. (Fig 3.1) It is surrounded by corridors on all sides and is approached at either end a by a flights of steps in north and south. A thin layer of bitumen was applied to the bed of the Bath to ensure that water did not seep in. Water was supplied by a large well in an adjacent room. There was a drain for the outlet of the water. The bath was surrounded by sets of rooms on sides for changing cloth. Scholars believe that the ‘Great Bath’ was used for ritual bathing. Another structure here located to the west of the ‘Great Bath’ is the granary. It consists of several rectangular blocks of brick for storing grains. A granary has also been found at Harappa. It has the rows of circular brick platforms, which were used for threshing grains. This is known from the finding of chaffs of wheat and barley from here.

ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES

(i) Agriculture – The prosperity of the Harappan civilization was based on its flourishing economic activities such as agriculture, arts and crafts, and trade. The availability of fertile Indus alluvium contributed to the surplus in agricultural production. It helped the Harappan people to indulge in exchange, both internal and external, with others and also develop crafts and industries. Agriculture alongwith pastoralism (cattle rearing) was the base of Harappan economy.

The chief food crops included wheat, barley, sesasum, mustard, peas, jejube, etc. The evidence for rice has come from Lothal and Rangpur in the form of husks embedded in pottery. Cotton was another important crop. A piece of woven cloth has been found at Mohenjodaro. Apart from cereals, fish and animal meat also formed a part of the Harappan diet.

(ii) Industries and Crafts – The Harappan people were aware of almost all the metals except iron. They manufactured gold and silver objects. The gold objects include beads, armlets, needles and other ornaments. But the use of silver was more common than gold. A large number of silver ornaments, dishes, etc. have been discovered. A number of copper tools and weapons have also been discovered. The common tools included axe, saws, chisels, knives, spearheads and arrowheads. It is important to note that the weapons produced by the Harappans were mostly defensive in nature as there is no evidence of weapons like swords, etc. Stone tools were also commonly used. Copper was brought mainly from Khetri in Rajasthan. Gold might have been obtained from the Himalayan river-beds and South India, and silver from Mesopotamia. We also have the evidence of the use of the bronze though in limited manner. The most famous specimen in this regard is the bronze ‘dancing girl’ figurine discovered at Mohenjodaro. It is a nude female figure, with right arm on the hip and left arm hanging in a dancing pose. She is wearing a large number of bangles.

Pottery-making was also an important industry in the Harappan period. These were chiefly wheel-made and were treated with a red coating and had decorations in black. These are found in various sizes and shapes. The painted designs consist of horizontal lines of varied thickness, leaf patterns, palm and papal trees. Birds, fishes and animals are also depicted on potteries.

(iii) Trade – Trading network, both internal (within the country) and external (foreign), was a significant feature of the urban economy of the Harappans. As the urban population had to depend on the surrounding countryside for the supply of food and many other necessary products, there emerged a village-town (rural-urban) interrelationship. Similarly, the urban craftsmen needed markets to sell their goods in other areas. It led to the contact between the towns. The traders also established contacts with foreign lands particularly Mesopotamia where these goods were in demand.

The inscriptional evidence from Mesopotamia also provides us with valuable information on Harappan contact with Mesopotamia. These inscriptions refer to trade with Dilmun, Magan and Meluhha. Scholars have identified Meluhha with Harappan region, Magan with the Makran coast, and Dilmun with Bahrain. They indicate that Mesopotamia imported copper, carnelian, ivory, shell, lapis-lazuli, pearls and ebony from Meluhha. The export from Mesopotamia to Harappans included items such as garments, wool, perfumes, leather products and sliver. Except silver all these products are perishable. This may be one important reason why we do not find the remains of these goods at Harappan sites.

SOCIAL DIFFERENTIATION

The Harappan Society comprised of people following diverse professions. These included the priests, the warriors, peasants, traders and artisans (masons, weavers, goldsmith, potters, etc.) The structural remains at sites such as Harappa and Lothal show that different types of buildings that were used as residence by different classes. The presence of a class of workmen is proved by workmen quarters near the granary at Harappa. Similarly, the workshops and houses meant for coppersmiths and beadmakers have been discovered at Lothal. Infact, we can say that those who lived in larger houses belonged to the rich class whereas those living in the barracks like workmen quarters were from the class of labourers.

Harappan people loved to decorate themselves. Hair dressing by both, men and women, is evident from figurines found at different sites. The men as well as women arranged their hair in different styles. The people were also fond of ornaments. These mainly included necklaces, armlets, earrings, beads, bangles, etc., used by both the sexes. Rich people appear to have used the ornaments of gold, silver and semi precious stones while the poor satisfied themselves with those of terracotta.

RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES

Our knowledge on the religious beliefs and practices of the Harappans is largely based on the Harappan seals and terracotta figurines available to us. The Harappan religion is normally termed as animism i.e., worship of trees, stones etc. A large number of terracotta figurines discovered at the Harappan sites have been associated with the worship of mother goddess. Many of these represent females adorned with a wide girdle, loin cloth and necklaces. They wear a fan-shaped head dress. In some cases the female is shown with an infant while there is one that shows a plant growing out of the uterus of a woman. The latter type probably symbolizes the goddess of earth. There are many scholars who refer to the worshiping of linga (phallus) and yoni (female sex organ) by the Harappans but some are doubtful about it.

The evidence of fire worship has also been found at some sites such as Kalibangan and Lothal. At Kalibangan, a series of raised brick platforms with pits containing ash and animal bones have been discovered. These are identified by many scholars as fire altars.

This also shows that the Harappans living in different areas followed different religious practices as there is no evidence of fire-pits at Harappa or Mohanjodaro.

THE SCRIPT

The Harappans were literate people. Harappan seals, are engraved with various signs or characters. Recent studies suggest that the Harappan script consists of about 400 signs and that it was written from right to left. However, the script has not been deciphered as yet. It is believed that they used ideograms i.e., a graphic symbol or character to convey the idea directly. We do not know the language they spoke, though scholars believe that they spoke “Brahui”, a dialect used by Baluchi people in Pakistan today. However further research alone can unveil the mystery and enable us to know more about the Harappan script.

DECLINE OF THE HARAPPAN CIVILIZATION

The Harappan Civilization flourished till 1900 BC. The period following this is marked by the beginning of the post-urban phase or (Late Harappan phase). This phase was characterised by a gradual disappearance of the major traits such as town-planning, art of writing, uniformity in weights and measures, homogeneity in pottery designs, etc. The regression covered a period from 1900 BC–1400 BC There was also the shrinkage in the settlement area. For instance, Mohenjodaro was reduced to a small settlement of three hectares from the original eighty five hectares towards the end of the Late phase. The population appears to have shifted to other areas. It is indicated by the large number of new settlements in the outlying areas of Gujarat, east Punjab, Haryana and Upper Doab during the later Harappan period.

(i) It is suggested by some scholars that natural calamities such as floods and earthquakes might have caused the decline of the civilization. It is believed that earthquakes might have raised the level of the flood plains of the lower course of Indus river.

(ii) Increased aridity and drying up of the river Ghaggar-Harka on account of the changes in river courses, according to some scholars, might have contributed to the decline. This theory states that there was an increase in arid conditions by around 2000 BC. This might have affected agricultural production, and led to the decline.

(iii) Aryan invasion theory is also put forward as a cause for the decline. According to this, the Harappan civilization was destroyed by the Aryans who came to India from north-west around 1500 BC. However, on the basis of closer and critical analysis of data, this view is completely negated today

CHALCOLITHIC COMMUNITIES OF NON-HARAPPAN INDIA

The important non-Harappan chalcolithic cultures lay mainly in western India and Deccan. These include Banas culture (2600BC–1900 BC) in south-east Rajasthan, with Ahar near Udaipur and Gilund as its key sites; Kayatha culture (2100BC–2000 BC) with Kayatha in Chambal as its chief site in Madhya Pradesh; Malwa Culture (1700BC–1400BC) with Navdatoli in Western Madhya Pradesh as an important site, and Jorwe culture (1400BC– 700BC) with Inamgaon and Chandoli near Pune in Maharashtra as its chief centres. The evidence of the chalcolithic cultures also comes from eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Bengal. It may be noted that the non-Harappan Chalcolithic cultures though flourished in different regions they were marked by basic uniformity in various aspects such as their mud structures, farming and hunting activities, use of wheel made pottery etc. The pottery of these chalcolithic cultures included ochre coloured pottery (OCP), black-and-red ware (BRW) and has been found in the shape of various kinds of bowls, basins, spouted jars with concave necks, dishes on stand, etc.

TOOLS, IMPLEMENTS AND OTHER OBJECTS

The chalcolithic cultures are characterised by the use of tools made of copper as well as stone. They used chalcedony, chert etc. for making stone tools. The major tools used were long parallel-sided blades, pen knives, lunates, triangles, and trapezes. Some of the blade tools were used in agriculture. Main copper objects used include flat axes, arrowheads, spearheads, chisels, fishhooks, swords, blades, bangles, rings and beads. Beads made of carnelian, jasper, chalcedony, agate, shell, etc. frequently occur in excavations. In this context, the findings from Daimabad hoard are noteworthy. The discovery includes bronze rhinoceros, elephant, two-wheeled charriot with a rider and a buffalo. These are massive and weigh over sixty kilograms. From Kayatha (Chambal valley) also copper objects with sharp cutting edges have been recovered. These reflect the skills of the craftsmen of the period.

SUBSISTENCE ECONOMY

The people of these settlements subsisted on agriculture and cattle rearing. However, they also practised hunting and fishing. The main crops of the period include, rice, barley, lentils, wheat, jawar, coarse gram, pea, green gram, etc. It is to be noted that the major parts of this culture flourished in the zone of black soil, useful mainly for growing cotton. Skeletal remains from the sites suggest the presence of domesticated and wild animals in these cultures. The important domesticated animals were cattle, sheep, goat, dog, pig, horse, etc. The wild animals included black buck, antelope, nilgai, barasinga, sambar, cheetah, wild buffalo and one-horn rhino. The bones of fish, water fowl, turtle and rodents were also discovered.

HOUSES AND HABITATIONS

The Chalcolithic cultures were characterised by rural settlements. The people lived in rectangular and circular houses with mud walls and thatched roofs. Most of the houses were single roomed but some had two or three rooms. The floors were made of burnt clay or clay mixed with river gravels. More than 200 sites of Jorwe culture (Maharashtra) have been found. The settlements at Inamgaon (Jorwe culture) suggests that some kind of planning was adopted in laying of the settlement.